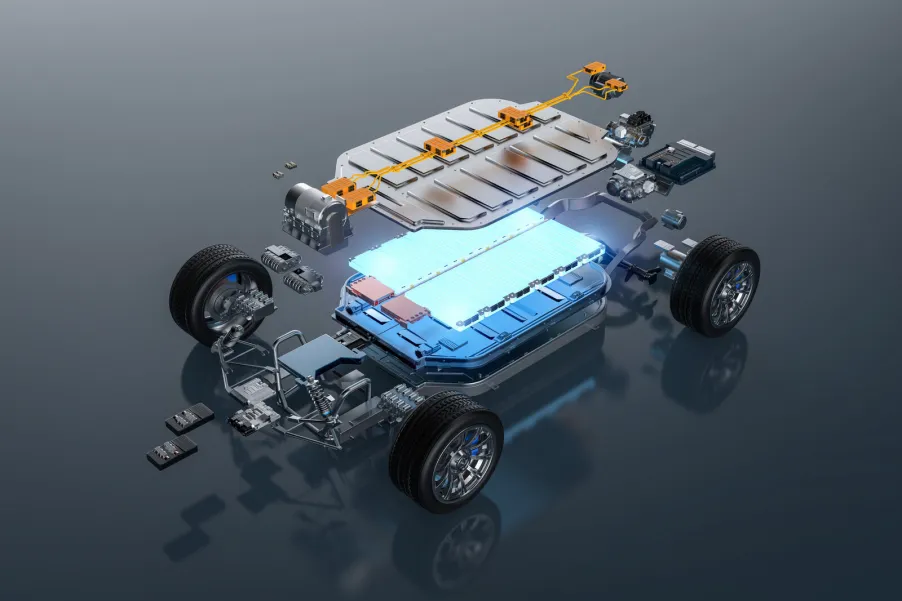

What happened and who’s affected

An EV technology supplier that had been collaborating with Stellantis the parent of Jeep, Dodge, Chrysler, Ram and others has filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, initiating liquidation of its U.S. operations. Multiple industry reports point to Exro as the supplier in question; the company had been working with Stellantis on coil-driver tech aimed at improving EV efficiency and performance before abruptly ceasing U.S. activity and moving to wind down assets under Chapter 7. Unlike Chapter 11 (restructuring), Chapter 7 typically means the business shuts down and sells assets to satisfy creditors, with projects and contracts in the U.S. likely terminated or transferred.

Why this matters for Stellantis’ EV roadmap

For Stellantis, the immediate operational impact may be limited large automakers diversify suppliers and maintain contingency plans—but the timing underscores how fragile parts of the EV supply chain remain in late 2025. Stellantis had been evaluating Exro’s technology across potential Jeep/Ram/Chrysler applications to make EVs “more affordable and fun to drive” without a full platform overhaul—precisely the kind of bolt-on efficiency gain that helps legacy brands bridge today’s cost pressure and tomorrow’s scale. That line of exploration now faces turbulence as the supplier’s U.S. assets head to liquidation, potentially delaying test milestones, validation loops, or tech-transfer paths depending on how intellectual property and hardware are handled in court.

What we know about the supplier’s decline

Public reporting portrays a company under mounting strain through 2024–2025: revenue far below spend, layoffs, and executive turnover. Exro reportedly posted a net loss near $79 million on about $3 million in revenue, cut roughly 60 employees, and saw its CEO depart in 2025 all red flags for a venture racing to commercialize advanced power electronics into a tightening capital market. Notably, coverage indicates the bankruptcy applies to U.S. operations, with Canadian activities described as unaffected—an important nuance for any cross-border licensing or IP arrangements.

Chapter 7 vs. Chapter 11: the EV twist

The distinction matters. Chapter 11 gives a supplier breathing room to restructure and keep shipping parts (think debtor-in-possession financing, continuity plans, customer support agreements). We’ve seen major Tier-1s take that path this year as tariffs, inflation, and program delays squeeze cash. Chapter 7, by contrast, typically means no operational continuity: programs pause or end, employees disperse, and assets (including test rigs, prototypes, software, and patents) are queued for sale by a trustee. For Stellantis, that can translate into:

- Validation disruption: re-sourcing and re-testing components that were near pilot.

- IP uncertainty: ensuring licensing rights or access to code and control algorithms survive the liquidation.

- Schedule pressure: re-aligning calibration and durability cycles if a substitute supplier needs to replicate test evidence.

Context: elsewhere in Stellantis’ supply web, deals have been revised or canceled (e.g., graphite offtake), highlighting an industry recalibrating EV bets amid softer demand and higher costs.

How big is the risk to customers and dealers?

Short-term risk to retail customers is low because this technology was in development/validation rather than in mass-produced, on-sale vehicles. There’s no indication of field repairs or recalls tied to this supplier’s hardware. For dealers, the main effect is indirect: if a given EV or hybrid variant was counting on marginal efficiency gains (range, performance, cost), timelines could shift while Stellantis sources comparable functionality or drops that feature from a near-term release. The cost impact for the automaker may be modest initially, but repeated supplier failures raise program risk premiums industry-wide.

The broader EV supplier squeeze

This case lands in a year where multiple suppliers have hit financial turbulence as higher rates, tariff frictions, and slower-than-hoped EV adoption complicate business plans. Some, like major Tier-1s, have sought Chapter 11 protections to restructure while operating; others simply liquidate. Even when an automaker offers support mechanisms (temporary tariff aid, volume smoothing, or accelerated payments), the most capital-intensive startups—especially those pre-revenue or pre-scale—are vulnerable to a single program slip.

What Stellantis does next

Expect Stellantis to follow the standard playbook:

- Lock down IP exposure and tooling—confirm rights to any software, algorithms, or prototypes developed under the NDA period; retrieve fixtures or data sets if housed at the supplier.

- Pursue alternative tech paths—either a direct re-source to another controls supplier, or a pivot to in-house solutions where feasible. Recent moves show Stellantis actively pruning and reshaping supply deals across the battery and e-power electronics stack.

- Protect near-term launches—prioritize EV and range-extended models that are closest to job-1, trimming optional features if they complicate certification or SOP timing.

- Communicate quietly—no need for consumer-facing statements unless products in market are affected; internal program gates and supplier councils handle the heavy lifting.

Investor and industry read-through

For investors, Chapter 7 here is less about Stellantis’ solvency and more about execution friction in electrification’s middle innings. Stellantis continues to invest in European and North American EV parts capacity while reassessing suppliers that don’t meet performance, cost, or timing targets. A single supplier liquidation rarely derails a platform, but it does add cost and schedule noise. The bigger signal: EV supply chains are still normalizing and OEMs will keep oscillating between external innovation (startups, specialty Tier-2s) and verticalization when the economics favor bringing tech in-house.

Could this ripple beyond Stellantis?

Yes—two ways. First, contagion risk: lenders may tighten terms for early-stage EV tech suppliers, raising the bar for purchase orders or milestone payments and nudging more of them toward Chapter 11 or 7 if timelines slip. Second, program conservatism: OEMs may pare back experimental feature sets in favor of proven components for 2026–2027 launches, prioritizing manufacturing stability over incremental gains. None of that stops the EV transition; it does make it bumpier and more cost-sensitive.

Conclusion

A Stellantis-linked EV parts supplier filing Chapter 7 is a reminder that supply chain resilience not just battery breakthroughs will define the next two years of the EV story. For Stellantis, this is a solvable hiccup, not an existential detour. The company has other battery and e-drive initiatives in flight and can re-source or internalize the affected tech. For suppliers, the message is stark: cash runway, OEM alignment, and validation speed are as critical as the innovation itself.